Since this blog was published, the Government of Luxembourg has contacted MDAC to confirm that it has written to Amazon 'urging them to make use of their right to control and delete any content that can be found on their websites that violates the fundamental rights of any group of persons...especially those of persons with disabilities.' You can read Government's letter to MDAC by clicking on the link HERE. MDAC commends and encourages these efforts, but calls for greater international pressure on Amazon and others not to violate the fundamental rights of any group for any commercial or other purpose.

Last week Twitter went completely mental [sic] when two large British retailers - Asda and Tesco – were found selling fancy dress costumes called “mental patient” and “psycho ward” on their websites. Do you have to be bonkers not to find the costumes funny? Or were the managers of the supermarkets totally insane to sell these products in the first place?

Marketing madness

Asda forced to withdraw from sale

Asda forced to withdraw from sale

A psycho suit is as unacceptable as selling an “Islamic terrorist” outfit, complete with fake beard and machine gun. Both costumes perpetuate stereotypes: that people with psycho-social (mental health) disabilities are by default dangerous and Muslims are terrorists. Obviously. The trouble with such oppressive stereotypes is that they pedal discriminatory attitudes about marginalised sections of society, and this results in real-life discrimination.

British disability NGOs took to Twitter when the sale of the costumes was uncovered. They argued that the costumes caused offence. Having received a £25,000 donation from Asda by way of pseudo-apology, the mental health charity Mind said that the retailers should in the future “consider taste and decency on mental health grounds, to avoid fuelling stigma and discrimination that are so damaging for large numbers of the population.” Some commentators in the media went for the angle that it was just a ‘joke’ being taken too seriously. Others put it down to a failure of business ethics, whatever that means.

The striking thing about the media reportage has been the entire focus on the need to avoid offence, such as the opinion piece in The Guardian by Labour party ex-spin doctor turned mental health champion Alastair Campbell. I think that the issues are far broader and more important than taste, ethics, offence and wishy-washy stigma.

A joke. Seriously?

Peddling stereotypes

Peddling stereotypes

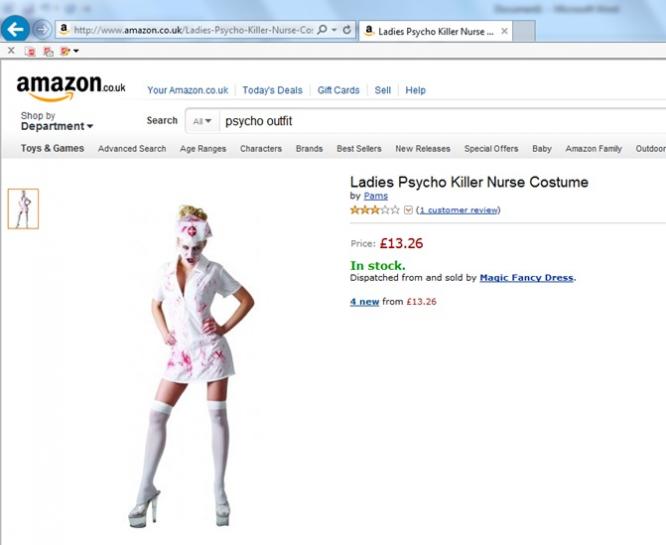

When the news story was breaking, we at MDAC did some quick searches on Amazon.com, and its affiliate UK site. We found all sorts of questionable party outfits. How could you resist a “Killer Psycho Sideshow Clown Halloween Costume”? If that’s a bit too macho perhaps, try a “Ladies Psycho Granny Costume”. For something less revealing but equally glamorous, the “Psycho-delic Straight Jacket Adult Halloween Costume” is for you.

Colleagues and I found it difficult to write off these items simply as jokes. One of MDAC’s priorities over recent years has been to expose the widespread use of straps, cage beds, forced drugging and other forms of restraint used against people detained in psychiatric hospitals. In fact our very first publication back in 2002 was about cage beds. Last year our partner NGO the League of Human Rights and we won a case representing Mr Bureš, a cellist from the Czech Republic. He was put in restraints when detained in a sobering-up centre. His elbow was damaged, severely affecting his ability to continue playing the cello, and the European Court of Human Rights found this to amount to inhuman and degrading treatment.

We decided to buy one of the straitjacket costumes. Perhaps one day it will be an item in the museum of discrimination. But I hope even more that it will be an exhibit in a court case against Amazon, or against the government of Luxembourg, where the company is based. And we won’t simply be arguing that the costume ‘causes offence,’ but rather that it violates human rights laws.

‘Costumes’ and human rights

As I’ve written previously, human rights can impact on corporations, or “non-state actors” as human rights geeks like to say. So why should Amazon take human rights seriously? The European branch of the company is based in the EU Member State of Luxembourg, for tax-avoidance reasons (the European Commission is currently investigating). Luxembourg is a state party to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). The CRPD requires the Luxembourgish government to do two things in relation to this unfolding psycho drama. MDAC set these out in a letter to the Prime Minister today.

First, Luxembourg must “adopt immediate, effective and appropriate measures” to “combat stereotypes, prejudices and harmful practices relating to persons with disabilities, including those based on sex and age, in all areas of life”. These instructions are found in Article 8 of the CRPD, which sets out awareness-raising of disability issues throughout society. The Luxembourgish government needs to demonstrate what sort of measures it is taking to combat the psycho suits stereotypes, including the gender-based stereotypes that have now come to its attention.

Second, the Luxembourg government must “take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination on the basis of disability by any person, organisation or private enterprise”. This duty is found in Article 4(1)(e) of the Convention. Amazon is a private enterprise.

Inducing sales by stereotyping people with mental disabilities?

Inducing sales by stereotyping people with mental disabilities?

But does the sale of psycho costumes constitute discrimination? The CRPD defines discrimination as “any distinction, exclusion or restriction on the basis of disability which has the purpose or effect of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal basis with others, of all human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field.”

The whole purpose of selling these costumes is to induce a sale on the stereotype. These products are named “mental patient costume” and “ladies psycho killer nurse costume” which surely is good evidence of the seller’s intention to create a distinction on the basis of disability. As the definition makes clear, harm need not be intended (and there is no evidence of this anyway): it matters only that the discrimination results in impairing the enjoyment of a right. We then need to identify the right whose enjoyment has been impaired. This surely is the right to live in the community.

The right to live in the community is one of the most difficult rights to achieve in any society at any time. It requires policy leadership, creativity, budget reallocation and a long-term commitment to inclusion and equality of people with disabilities. Community living is made more difficult in an environment polluted by attitudinal toxicity: whether this be vocal neighbours protesting that they do not want people with disabilities living next to them (as is currently the discourse in Hungary), or whether it is drunk teenagers dressed in Halloween costumes as axe-wielding madwomen.

Many people all over the world with mental health issues are already faced by a collapse of familial structures. They live in poverty due to employment discrimination and austerity budget cuts to social security. They are faced with growing rates of hate crimes. In these circumstances, no reasonable company would continue to sell products that tacitly promote human rights violations. And no reasonable government would be silent.

Human rights imply obligations, accountability and remedies. MDAC is currently seeking legal advice about the liability of the Luxembourg government under the CRPD, and under European Union law. In the meantime we have written to the Luxembourgish Prime Minister, reminding him that he must not pretend that this is not only a problem of sensitivities or business ethics. It is about the obligation that governments have to create inclusive societies in which we can all live, without fear of hatred or worse.